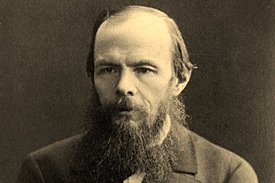

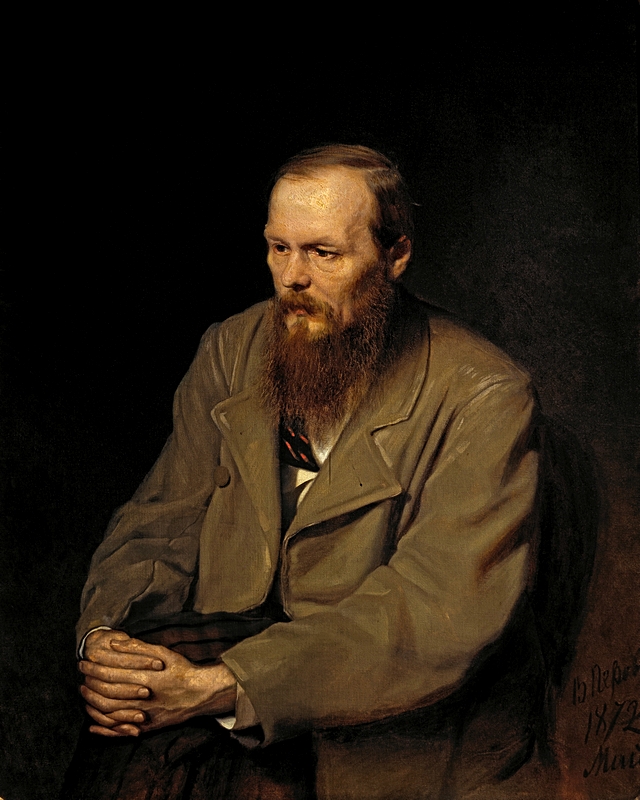

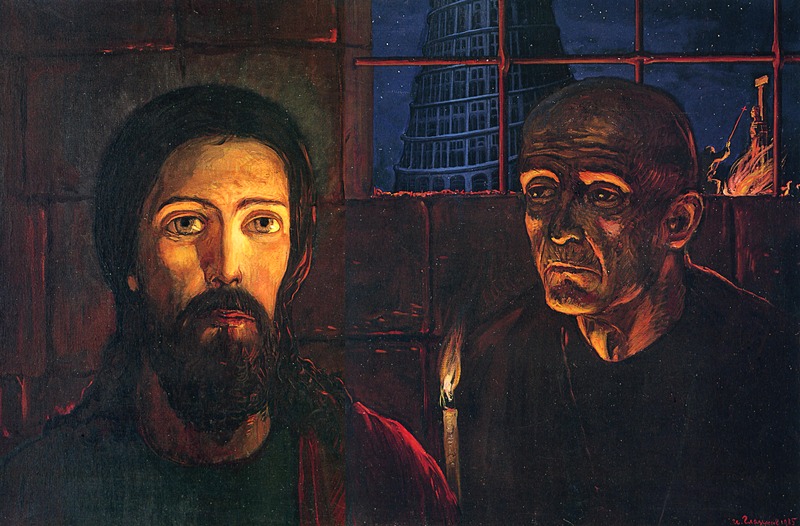

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Born: Moscow - 11 November 1821

Died: Died: St. Petersburg - 9 February 1881

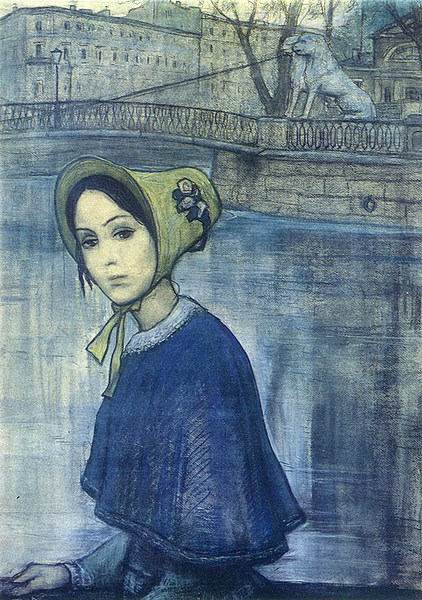

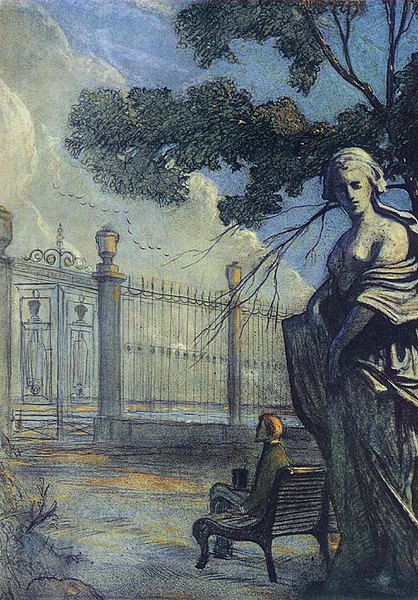

Fyodor Dostoevsky was the most popular and influential novelist of 19th century Russian literature. While Tolstoy may be more revered by posterity for his artistry and style, Dostoevsky's work, especially Crime and Punishment, had an impact that went far beyond the borders of the Russian Empire and the confines of the novel, shaping modern philosophical and political thought, as well as the burgeoning study of psychology. St. Petersburg, particularly its downtrodden, working-class neighborhoods, is integral to his work, and he has provided for posterity an urban portrait as unforgettable as Dickens's London or Joyce's Dublin.

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was born in Moscow in 1821, the second child of Mikhail Andreevich Dostoevsky and Maria Fyodorovna Dostoevskaya (neé Nechayeva). His father, of Lithuanian origin, had run away from home in his youth to avoid joining the clergy and studied to become a doctor at the Imperial Medical-Surgical Academy in Moscow. His mother's family were merchants. When Dostoevsky was born, his father was working at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in the northern suburbs of Moscow, and the writer's childhood home was in the grounds of the hospital.

Soon after Dostoevsky's birth, his father was made a collegiate assessor, which raised him to the lower ranks of the aristocracy. The family acquired a small estate near Moscow, where they usually spent the summer. Dostoevsky's father was extremely religious and strict with his children, but the family also had access to a wide variety of contemporary literature both foreign and Russian. Fyodor and his elder brother Mikhail were both sent to elite Moscow boarding schools, to pay for which their father took on extra patients and borrowed from relatives. However, when Fyodor was 15, his mother fell ill with tuberculosis, and Dostoevsky was sent to St. Petersburg to study at the Nikolayev Military Engineering Institute (in the Engineer's or Mikhailovsky Castle. His mother died the following year, and in 1839 his father also died from an apoplectic stroke, leaving Dostoevsky an 18-year-old orphan.

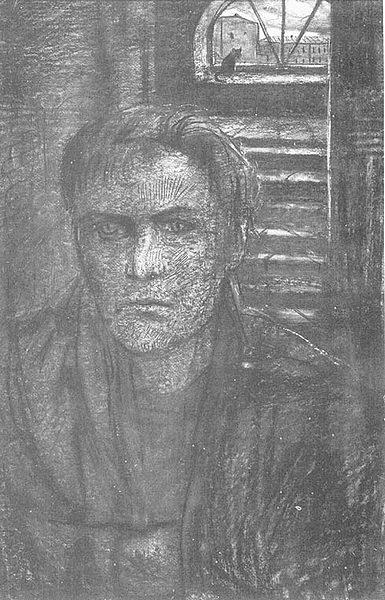

Although he had little aptitude for mathematics or engineering, preferring the arts and literature, and he was congenitally unsuited to military discipline, Dostoevsky nonetheless completed his studies and graduated in 1843, becoming a Second Lieutenant of Engineers. He would resign his commission the following year. During his studies, Dostoevsky had begun to write drama and short stories, none of which have survived. His first published works, the year of his graduation, were translations, of Balzac's Eugénie Grandet and Sand's La dernière Aldini. Enjoying the social and cultural life of a young officer in St. Petersburg's, with regular attendances at theatre and concerts and expensive apartments, Dostoevsky quickly began to live well beyond his means, and the situation was exacerbated when he discovered casinos, beginning a lengthy and disastrous career as a gambler. In an effort to cope with his burgeoning expenses, he decided to write a novel.

His first novel, Poor Folk, was completed in March 1845. A story of St. Petersburg's educated lower-middle classes living in desperate poverty, it was championed by the poet Nikolay Nekrasov and the critic Vissarion Belinsky, who proclaimed it Russia's first "social novel". The novel proved a healthy success with liberal critics and the public, but did little to alleviate Dostoevsky's financial woes. Moreover, his second novel, The Double, published almost simultaneously with Poor Folk in early 1846, was roundly dismissed by critics and public alike. Dostoevsky continued to write and publish in Petersburg journals short stories and novellas, but failed to rediscover the acclaim of his first work.

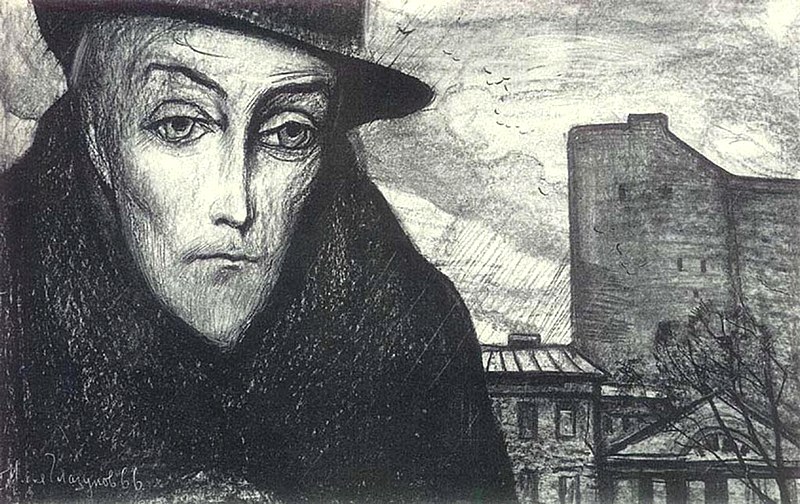

In this period, Dostoevsky became interested in the writings of French utopian socialists like Charles Fourier and Etienne Cabet. He joined the Petrashevsky Circle, a diverse group of progressive writers, intellectuals and minor officials formed to share and discuss contemporary European philosophy, much of which was banned at the time by the Tsarist government. Unlike Belinsky, who had initially introduced him to these ideas, Dostoevsky remained a devout Christian, and the Petrashevsky Circle roundly, while against serfdom and Tsarist rule, roundly rejected revolution and violent protest. Nonetheless, in a panic after the numerous European revolutions of 1848, Nicholas I orchestrated a crackdown on radical groups, and members of the circle including Dostoevsky were arrested on 23 April 1849.

Dostoevsky was held in the prisons of the Peter and Paul Fortress for four months while an investigative committee headed by the Tsar himself discussed the case. Eventually, the "conspirators" were sentenced to death by firing squad. Instead, they were subjected, on 23 December 1849, to a hideously homiletic mock execution on Semenovskaya Ploshchad (now Pionerskaya Ploshchad) where, already line up in front of the firing squad, they were redeemed at the last minute by the arrival of a car bearing a letter from the Tsar that commuted their sentences to exile and hard labour. Their crime, it should be noted again, was the dissemination of subversive literature.

Dostoevsky served just over five years in a labour camp at Omsk in Siberia. He had begun to suffer epileptic fits some time around his graduation, and his health continued to deteriorate under the harsh conditions of the camp. During his incarceration he was allowed to read only the New Testament, except during the periods when he was hospitalized, when he had access to journals and some novels. On his release in 1854, he was obliged to serve in the military for a further five years in the towns of Semipalatinsk in Kazakhstan and Barnaul in Western Siberia. During this period, he continued to write but was unable to publish his works. He also met, fell in love with and married his first wife, Maria. Their marriage was not a happy one, their incompatibility exacerbated by Dostoevsky's continuing ill health (he had regular seizures) and poverty, and they mostly lived apart.

In 1859, due to the poor state of his health and his repeated protests of remorse, Dostoevsky was eventually released from military service and allowed to return to St. Petersburg. The following year, he was able to publish several of the works he had written in the previous decade, most notably the first parts of The House of the Dead, a fictionalized account of his time in the labour camp. With his brother Mikhail's assistance, Dostoevsky established the literary journal Vremya ("time") which, as well as publishing further parts of The House of the Dead, an immediate success with the public and recognized as the first in a long line of Russian prison novels, and a number of Dostoevsky's short stories, also printed the first Russian translations of several tales by Edgar Allen Poe. The journal was a financial and critical success, but was banned in 1863 for an article that discussed the January uprising in Poland.

In 1862 and 1863, Dostoevsky travelled widely in Europe, visiting Switzerland, northern Italy, France and Germany. His impressions were mostly negative, confirming his slavophile, nationalistic tendencies, and he managed to increase his financial difficulties by gambling in casinos, especially in Baden-Baden. In 1864, both his wife Maria and his brother Mikhail died of consumption. The latter had been, despite their ten years of separation, Dostoevsky's closest confidant and supporter, and his death left the writer in even worse financial straits, as he became the sole guardian of his brother's young family. Nonetheless, the same year he completed and published his first undisputed masterpiece, Notes from the Underground.

In 1865, plagued by creditors and struggling to feed his family, Dostoevsky conceived of two works that would investigate the moral and social aspects of drunkenness and inveterate gambling. In desperate need of funds, he managed to obtain advances from different sources for the two works. The first work gradually transformed into a polemic against radicalism and morphed eventually into Crime and Punishment, published in monthly installments from January to December 1866 in The Russian Messenger, the preeminent liberal literary journal that was simultaneously serializing Tolstoy's War and Peace. Struggling to complete the necessary chapters each month and fulfill his contract for the second work, The Gambler, Dostoevsky in desperation employed the services of a stenographer, Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina. Together, they managed to complete the heavily autobiographical The Gambler in only 26 days in October.

Dostoevsky and Snitkina married in St. Petersburg's Trinity Cathedral on 15 February 1867. Despite their unceasing financial difficulties and Dostoevsky's continued ill health, this second marriage proved far more harmonious, and Snitkina was an able and enthusiastic supporter of her husband's literary work. Eventually able to depart for their honeymoon in April, after Snitkina had sold all her valuables to help pay her new husband's debts, the couple spent the next four years travelling through Germany. Their first daughter, Sonya, was born in Baden-Baden in March 1868, but died three months later of pneumonia. A second daughter, Lyubov, was born in 1869, and this event supposedly inspired Dostoevsky to finally give up his ruinous gambling addiction.

With the success of Crime and Punishment and the comparative stability of his second marriage, Dostoevsky's literary output became less manic and more consistent. He produced a new novel roughly every three years, nearly all of which were serialized in The Russian Messenger, and he proved to be one of the rare writers whose later career produced equally if not more successful works than his first masterpieces. The Idiot (1868) and the novella The Eternal Husband (1870) were well received social melodramas with philosophical overtones, while Demons (1872) returned to the themes of radical politics and ideology. His final two novels, The Adolescent (1875) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880), combined intra-family drama with philosophical, political and spiritual inquiry, and the latter is almost universally recognized as Dostoevsky's supreme literary achievement, and one of the greatest novels ever written.

After returning to Russia in 1871, and Dostoevsky spent the final decade of his life in St. Petersburg with occasional sojourns in the spa towns of Ems in Germany and Staraya Russa in Novogorod Province (the model for the setting of The Brothers Karamazov). He and his wife successfully established their own publishing company to sell his works in book form, but Dostoevsky would continue to struggle with debt to the end of his life. He was also never free from official scrutiny, although he had long abandoned the radical politics of his youth and was a devoutly Christian conservative in his later years. He worked for a time on the journal The Citizen, but had to give up the job after twice being sued for his writings. Nonetheless, he was more or less fully admitted to St. Petersburg's cultural establishment, named an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and even briefly invited by the new Tsar Alexander II to tutor his sons.

His epileptic seizures continued to plague him, and in 1879 he was also diagnosed with pulmonary emphysema. He died of a pulmonary hemorrhage on 9 February 1881 in his apartments on Kuznechny Pereulok (now the Dostoevsky Memorial Museum. He was buried in the Tikhvin Cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, and his funeral was attended by tens of thousands of mourners.

Dostoevsky's significance as a writer is indisputable, and he was acknowledged as an influence by nearly every major novelist of the early 20th century, including Franz Kafka, Knut Hamsun and James Joyce. Nietzsche, Freud, Sartre and even Einstein all also singled out his works for exceptional praise. His works have been translated into 170 languages, and reading and processing Crime and Punishment in particular has become a right of passage for adolescent intellectuals all over the world. In Russia, his reputation has been treated with slightly less reverence, with prominent critics of his work including Vladimir Nabokov, Ivan Bunin and even his contemporary Leo Tolstoy. His works were never censored in the Soviet Union, but his strong religious convictions and the mystical conservatism of his later years meant that he was also never fully officially celebrated, and in St. Petersburg no memorial to him was erected until as late as 1997.

Nonetheless, his place in St. Petersburg's conscience and folklore is incontrovertible. No other writer is so thoroughly interwoven into the fabric of the city. The damning portrait of poverty and degeneration in the city that he painted in Crime and Punishment has an affectionately ironic resonance to this day, recalled in the crumbling courtyards and decaying communal apartments of the old tenement buildings that still make up much of St. Petersburg's historic centre. For better or for worse, Dostoevsky is the writer who most comprehensively encapsulates the city.