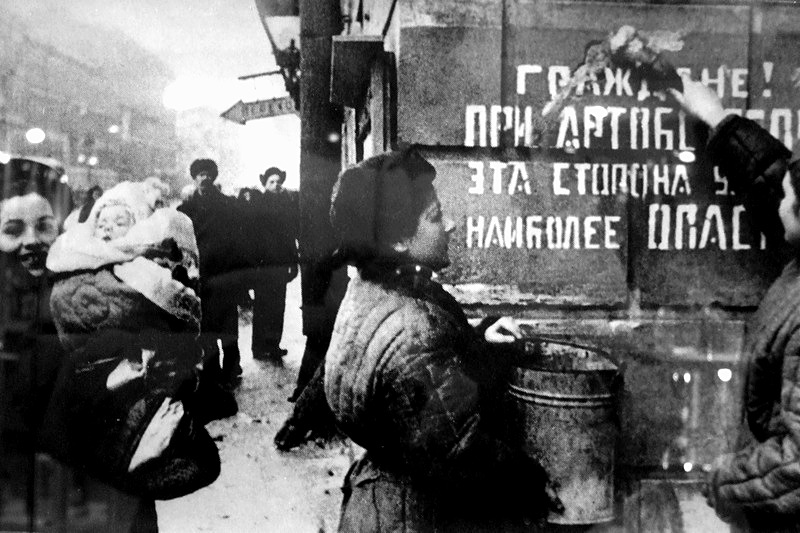

St. Petersburg (Leningrad) during the Great Patriotic War and the Siege (1941-1945)

In the early hours of 22 June 1941, Hitler's Germany attacked Stalin's Soviet Union. World War II had come to Russia. For Leningrad, the war meant blockade. Less than three months after the invasion, German Army Group North reached the outskirts of the city, in which some 3,000,000 people remained. Ultimate plans for the former imperial capital and cradle of the Bolshevik Revolution were to "wipe Leningrad from the face of the earth through demolitions." But first, the city had to surrender.

On 8 September, the Germans severed the last main road into the city and the most lethal siege in the history of the world began. For 872 days the blockade stretched on, during which the Germans sat entrenched, encircling the city only miles from the historic centre. They tossed bombs in its direction, prevented supplies from reaching the starving civilian population, and waited for capitulation. Hitler had optimistically predicted the city would "drop like a leaf," and menus were printed for the gala victory celebration that was planned at Leningrad's plush Astoria Hotel. Instead, civilians dropped like flies in an enclosed microcosm with virtually no food, no heat, no supplies, and no escape route. People keeled over dead in the streets by the thousands, malnourished, exhausted, and frozen. The Blockade of Leningrad resulted in the worst famine ever in a developed nation - over a million people died. But Leningrad never surrendered.

Perhaps most astounding was that amidst the hunger and the horror, with daily rations amounting to two thin slices of poor quality bread, great works of art were created. Dmitry Shostakovich spent the initial months of the siege trapped in the city of his birth, where he composed the first three movements of his searingly intense Seventh (Leningrad) Symphony, which he privately remarked was a protest not just against German fascism but also about Russia and all tyranny and totalitarianism. The symphony's most memorable performance occurred on 9 August 1942 in besieged Leningrad. As bombs fell nearby, a depleted, weakened, starving orchestra played to a packed concert hall of weakened, starving people. The performance was aired across the city via loudspeakers, some of which were directed toward German lines as an act of cultural resistance to atrocity.

Olga Bergholz became the voice of the Siege of Leningrad. By the time Olga found herself trapped within the besieged city, she had accumulated a typical Soviet biography: her former husband had been arrested on false charges and was subsequently executed during the Great Purge. Olga herself was imprisoned when pregnant in 1938; the child was "kicked out of her belly" by NKVD interrogators, but Olga survived and was released in July 1939. Now some two years later, amid shelling and starvation, she worked throughout the blockade at the only radio station still in operation. In her calm, reassuring voice she read her poems and those of other poets, and provided updates on bombings, fires, and news from the front. Most importantly, she gave her fellow Leningraders something to hold on to, something resembling hope:

To have survived this blockade's fetters,

Death daily hovering above,

What strength we have needed, neighbour,

What hate we've needed - and what love!

So much so that moods of doubt

Have shaken the strongest will:

"Can I endure it? Can I bear it?"

You'll bear it. You'll last out. You will.

Olga's husband, three aunts, and grandmother starved to death, but in her refusal to abandon hope, Bergholz stood for resistance to suffering and fear and she became a symbol of the city's strength and determination. Survivors said her familiar voice transmitted daily over the radio waves served as proof that the city had not surrendered and helped to keep them alive.

The Leningrad Blockade was lifted on 27 January 1944, but the war raged on for over a year, as Soviet soldiers marched hundreds of miles towards Berlin. On 7 May 1945, the German High Command signed the unconditional surrender documents and the war that had claimed the lives of 25 million Soviet citizens was finally over. Because of the heroism of its inhabitants who refused to submit despite unendurable conditions, Leningrad became the first Soviet city to receive the Hero City award in 1945.