Explore the Hermitage: An introduction to St. Petersburg's greatest museum

Time: approximately 3.5 hours

The Hermitage is St. Petersburg's most popular visitor attraction, and one of the world's greatest repositories of art and antiquities. For many travelers, it is the main reason to visit the city on the Neva, and its vast collections could theoretically take days if not weeks to explore. Most visitors, however, will wish to pack as much as possible into one morning or afternoon at the Hermitage, and this tour is designed to ensure that you miss none of the collection's spectacular highlights.

What is exactly is "The Hermitage"?

The Hermitage complex consists of five historic interconnected buildings, the largest and most impressive of which is the Winter Palace, which alone contains over 1,000 rooms, 1,700 doors, 1,900 windows, and 100 staircases. This vast palace, an imposing symbol of imperial might and prestige, was the official residence of the Romanov Tsars from 1762 until the revolution in 1917.

The Hermitage's amazing art collection:

- officially began in 1764 when Catherine the Great made her first bulk purchase of 225 paintings from a Berlin merchant, including thirteen Rembrandts and eleven Rubens. Ironically, the collection had originally been intended for Catherine's adversary, Frederick the Great of Prussia, but poor Frederick was forced to decline as his unsuccessful wars with Russia had resulted in a deficit of funds.

- increased exponentially as Catherine's diligent agents purchased massive lots of artwork across Europe. By the time of her death in 1796, she had amassed thousands of items including paintings, books, drawings, jewelry, coins, medals, sculpture, and copies of original Vatican frescoes, and had expanded the complex beyond the Small Hermitage to include the Large (Old) Hermitage and the Hermitage Theatre.

- continued to burgeon, causing Nicholas I to commission the New Hermitage, built between 1842 and 1851, with its Atlas-embellished entrance on Millionaya Street. This was the only part of the complex that was occasionally opened to the well-heeled public until after the Revolution in 1917.

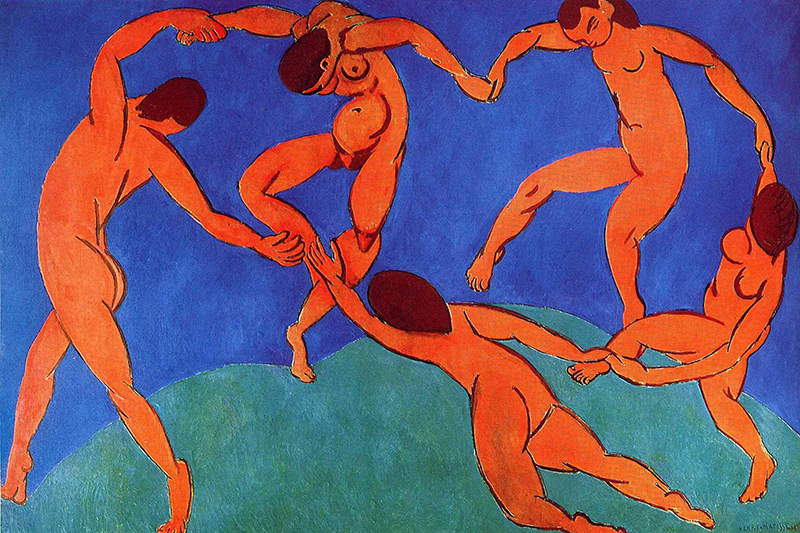

- greatly benefited from the confiscational mindset of the post-revolutionary period and actually increased threefold as many valuable private collections were expropriated by the state and deposited in the Hermitage. This influx of, among other things, Matisses, Picassos, and Gaugins helps to compensate somewhat for the artworks secretly sold off for hard currency by Stalin in the 1920s and 1930s.

It is ironic that the Hermitage – the grandest museum in the world, enormous and labyrinthine, with a collection of three million items sprawling across five buildings and admired by more than three million visitors per year – derives its name from the French word ermitage, meaning the 'abode of a hermit'. But this humble word takes us back to the collection's origins. In 1764, Empress Catherine the Great had the so-called Small Hermitage built as an adjunct to the Winter Palace with the purpose of creating a suitable retreat in which to peacefully admire her rapidly expanding art collection. Catherine, who acquired not simply individual paintings but entire collections with an avidity hard to surpass, thereby laid the foundations for this great museum, which was assiduously supplemented by a number of her successors. The result: an overwhelming collection of art housed in a magnificent palace graced with unsurpassed views. On this walking tour, we'll first promenade through the Winter Palace's opulent state rooms and then proceed on to view as many the collection's masterworks as possible.

We start our tour in magnificent Palace Square, behind us the yellow, classical curve of Carlo Rossi's General Staff Building (the east wing of which was recently acquired by the Hermitage and houses more modern additions to the museum's collection), before us Bartolomeo Rastrelli's imposing 250-meter-long baroque facade of the Winter Palace, a building as splendid and impressive as any of the masterpieces it houses. The current structure, with ebullient decoration in the form of Corinthian columns, larger-than-life statues and expressive window treatments is the fourth Winter Palace built on this spot – the first dates from 1712 and the reign of Peter the Great. It was Peter's daughter, the Empress Elizabeth, who commissioned Rastrelli's building in 1754, but as she died shortly before its completion in 1762, only her successors, beginning with Catherine the Great, were able to enjoy its pomp and circumstance.

Over the years, the interior has experienced a number of decorative changes, most significantly after a fire in 1837 that raged for over thirty hours and reduced much of its glory to ashes. However, the only notable external change has been that of color. Originally painted a pale yellow with white and gilded ornament, Nicholas I had the building redone in a dull red in 1837 and it was only after World War II that it attained its now seemingly iconic dusty green color with white and ocher embellishments. Taking a closer look at the structure, we note that Rastrelli implemented the architectural concept of the "noble floor" whereby the windows on the second floor, which housed rooms of state and the royal family suites, are taller than those of the floors above (intended for various courtiers) and below (minor and service rooms). We also note that our architect carefully avoided the monotony inherent in such a long, horizontal facade by skillfully interpolating columns and slightly-projecting bays and porticoes, thereby creating a pleasant impression of movement and variation.

Let's now enter through one of the arches adjoining the regal Main Gate, the elaborate black metalwork of which is decorated with the gilded monogram of Alexander III and his wife Maria Feodorovna and topped off by a double-headed eagle. Such obviously Tsarist embellishments were removed during Soviet times, but have since been restored in all their splendor. And let's continue along the main processional route that distinguished guests on ceremonial and state occasions used as they made their way to see the Tsar, and where the very architecture speaks the language of wealth, power, and opulence that is intended to impress.

Thus we proceed through the Great Courtyard, for whose leafy charm and babbling fountain we can thank that same Maria Feodorovna. It was she who in 1855 had this rectangular, Victorian-style garden laid out here in an area that was previously cobbled and lacked vegetation. And now let us enter the palace itself through the formal State Entrance (accessible from either side) and - after purchasing our tickets, picking up a map, and checking superfluous items in the coat room in the basement - continue on to the right through Rastrelli's majestic colonnaded Jordan Hall.

Ahead lies the grand Jordan Staircase, where the crowned statue of the Allegory of the State stands on a pedestal in a columned niche ready to greet us. This main staircase is one of the palace's few interior spaces that retains Rastrelli's original dynamic baroque style and it is a grand introduction to the extravagance of the Tsars. We note that this white marble staircase, which divides in front of the Allegory of State to meet up again on the second floor, is enhanced with a curving balustrade, swirling gold baroque decoration, and allegorical alabaster sculptures of Justice, Wisdom and other virtues theoretically embodied by the Russian Empire. This is the only space that extends the entire height of the Winter Palace, and the swirling, cloud-bedecked ceiling painting by Diziano Gasparo depicting levitating Olympian gods gives the impression of yet greater height. The design is basically symmetrical and where Rastrelli was not able to use windows due to the presence of adjoining rooms, he nonetheless manages to retain architectural symmetry by employing mirrors, which further increases the impression of space and light. Originally known as the Ambassadorial Staircase, as foreign envoys ascended it when they attended official ceremonies, it received its second name in the nineteenth century because the Imperial family used it to descend to the Neva River for the annual January celebration of Christ's baptism in the River Jordan.

The Jordan Staircase brings us up to the impressive rooms of state, where imperial receptions, official ceremonies, court festivities, and magnificent balls were held. Turning to the left at the top of the staircase we reach the Field Marshall Room (Room 193), the first in the so-called Great Enfilade, a series of spectacular state rooms designed to overwhelm those entering with the imperial glory and military might of the Russian Empire. This room and most of those following were revamped by the architect Vasily Stasov in a more classical style after the fire of 1837, which broke out here and destroyed great swaths of the Winter Palace. Conceived in honor of Russia's military leaders, the room fittingly contains full-length portraits of Russian Field Marshals (the highest military rank aside from generalissimo), most notably (from left to right) Kutuzov, Suvorov and Potemkin. Further motifs of military glory embellish the massive gilded bronze chandeliers and the grisaille paintings on the ceiling.

The next room in the Great Enfilade is the Small Throne Room (Room 194). This dramatic room, featuring crimson velvet wall panels embroidered with silver double-headed eagles and decorated with a plethora of gilt, also goes by the name of the Memorial Hall of Peter the Great. Somewhat incongruously, the throne, set on a dais and housed in a highly ornamented apse, was actually constructed for the relatively insignificant Empress Anna Ioannovna in the early 1730s (before us is a copy dating to 1797). But above the throne we note the more appropriate painting of a statuesque Peter accompanied by the allegorical figure of Glory, with a hovering cupid ready to place a crown upon Peter's royal head. The room also contains two large battle scenes from Peter's victorious northern war against Sweden. Let's see how many examples of his monogram (PP for Petrus Primus, or Peter the First, as he is known in Russia) we can detect among the motifs decorating the stucco capitals, pilasters and frieze reliefs. The number of double-headed eagles that, along with some lovely angels, bedeck the vaulted ceiling and diminish in size as they recede up into the vault, seems close to uncountable. In this appropriately regal atmosphere, diplomats congregated on New Year's Day to offer good wishes to the Tsar.

From here we pass into the opulent Armorial Hall (Room 195), which at over 1000 square meters, is one of the largest and most visually impressive rooms in the Winter Palace. This stunning duo-chromatic creation in gold and white was designed by Vasily Stasov in fine classical style after the 1837 fire and was intended for official ceremonies. Pairs of fluted gilt Corinthian columns interrupted by windows or mirrors support a slender balustrade that wraps around the symmetrical, well-proportioned room. The hall takes its name from the coats of arms of all the Russian provinces that embellish the enormous gilt bronze chandeliers. We should also admire the sculptural groups of early Russian warriors flanking the entrances to the hall.

Exiting to the left through the doorway in the middle of the hall, we reach the War Gallery of 1812 (Room 197). This narrow but long room houses 333 gold-framed portraits of distinguished military commanders instrumental in defeating Napoleon's Grand Armée and driving it back thousands of miles from Moscow to Paris. The thirteen empty frames represent those generals who were not available to sit in person and for whom no likeness could be found. To the left, most impressively, we see the dominating equestrian portrait of victorious Tsar Alexander I decked out in a dashing military uniform. Alexander is depicted against the distant background of Paris, mounted on a white stallion that Napoleon had presented to him back in friendlier times. In 1814, six years after receiving this gift, Alexander rode the steed into the subjugated French capital in triumph.

Exiting the War Gallery we now enter one of the most significant interior spaces in the entire Russian Empire – the monumental St. George Hall (Room 198) which served as the principal throne room for the Russian Tsars and was thus the scene of many of the Imperial court's formal ceremonies and elaborate receptions. As with the Armorial Hall, this space was redesigned by Stasov after the fire of 1837 who once again used classical proportions, symmetry and style – although this time with less gold and more white Italian carrara marble – to create a parade hall of considerable effect. Let's look down to admire the intricate parquet floor, made from sixteen different species of valuable wood, and then let's look up beyond the twenty-eight crystal and bronze chandeliers to the ceiling where we find the same pattern repeated in bronze. However our eyes keep reverting to the main focus of the hall – the majestic imperial throne that is set upon a dais and surmounted by a massive depiction of the two-headed imperial eagle (during Soviet times the throne was removed and a large map of the USSR hung in this most symbolic of places), all housed under an elaborate baldachin. Above this integrated composition in red and gold we find an appropriate marble bas-relief: St. George, Russia's patron saint, sits astride a prancing steed, his long spear making short work of the enemy dragon.

Continuing through the small room beyond the St. George Hall, we reach the long western wing of Catherine's original Hermitage. Let's take a look out the window at the charming enclosed garden. Wait, what floor are we on? Indeed, the second floor – this is Catherine's so-called Hanging Garden, as it is raised above ground level. During the dreadful starvation years of the Siege of Leningrad, curators grew vegetables here.

Proceeding north through the collection of medieval art with the garden to our right, we soon reach the delicate Pavilion Hall (Room 204), designed in the mid-19th century by Andrei Stakenschneider on the site of Catherine's earlier Small Hermitage pavilion. Stakenschneider, Russia's most renowned Eclectic architect, here combines a variety of architectural elements derived from Classical Antiquity, the Renaissance, and the Orient to create a fanciful, light-filled space. The pavilion is adorned with twenty-eight glittering chandeliers and an arcade of fluted white columns that supports a graceful gallery with gold leaf embellishments. On the floor in the niche we see a nineteenth century copy of an ancient Roman mosaic featuring the head of Medusa encircled by nautical themes such as Neptune with his trident and imaginative sea creatures.

But the centerpiece of the Pavilion is the magnificent Peacock Clock, commissioned for Catherine by one of her favorites, Gregory Potemkin, whose portrait we admired back in the Field Marshall's Hall. This gilded extravaganza, designed in the mid-eighteenth century by the English master James Cox, features a plethora of moving wildlife including a dragonfly, owl, squirrel, and most impressively a self-confident peacock perched in an oak tree who, at the appropriate time spreads its voluminous feathers, rotates 360 degrees, and makes a stately bow, after which the nearby rooster crows. The entire mechanism still runs like, ahem, clockwork, although only at a few specific scheduled times. But wait, where is the actual clock? If you look closely, you'll see the dial with roman numerals incorporated into the head of a mushroom to the right of the squirrel.

Ach, how delightful it would be to relax in this lovely pavilion and enjoy a cup of tea at one of the mosiac-embellished tables with a delightful princess or two. But, there is no such rest to be had for the weary and so we must push on, exiting the Pavilion on the further side of the Clock and thus leaving the the Small Hermitage to step into the awe-inspiring world of Italian art sequestered in the Large (Old) Hermitage. What a treasure house lies before us!

Let's first glance at the Madonna with Child and Two Angels (c. 1385) by the Sienese master, Paolo di Giovanni Fei (c. 1345 – c. 1411), immediately to the left of the door in Room 207. This lovely work, glittering in gold, displays all the beauty of the late-Gothic style, with graceful, elegant forms, decorative patterning, limited linear perspective, and stylized, elongated and somewhat unrealistic proportions. There is no visual interaction between mother and child. We'll keep this regal work in mind as we proceed.

Coming to Room 209, let's stop before the fresco The Virgin and the Child with Sts. Dominic and Thomas Aquinas (c. 1425) by the Dominican monk Fra Angelico (1395 – 1455), whose name means the Angelic Friar and who is renowned for his beautiful frescoes that always centered on religious themes. Ah, indeed, the early Renaissance is breaking in upon us! Our devout monk from Florence, that birthplace of the Renaissance, pioneered many of the stylistic trends that characterize this art style and which we can see captured in this painting, including the rational treatment of pictorial space, and the use of light and shadow to create the illusion of volume. In contrast to our previous regal Madonna, the sky here is not gilded but a powdery blue, the forms are solid, there is a natural three-dimensionality to the figures, garments are believably draped, and the relatively well-proportioned child sits firmly on Mary's sturdy lap. Although Mary herself is charmingly idealized, we can admire the individuality and character that Angelico, in good Renaissance fashion, lends to the figures of St. Dominic, the founder of the Dominican order with a lily in his right hand, and St. Thomas Aquinas, the great theologian who holds a copy of the Bible open to the Psalms.

Now let us move on to that Master of the High Renaissance, that Universal Renaissance Man, the grand Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519), two of whose approximately ten surviving paintings are located before us in Room 214. First we come to Madonna and Child with Flowers (Benois Madonna), a rare early work by the young Leonardo, dating from approximately 1478. What freshness! What spontaneity! Look at the obvious affection shining from Mary's girlish face as she plays with her young child, handing him a flower that he curiously, yet earnestly examines. Depicted in contemporary dress and hairstyle, Mary's happy expression is a virtual novelty among the practically endless iconography of the Madonna and Child. Yet this charming genre scene contains a hidden somber tone. The painting centers on a play of gestures, with three hands entwined around a four-petaled flower from the Cruciferae family: a reference to Christ's death on the Cross.

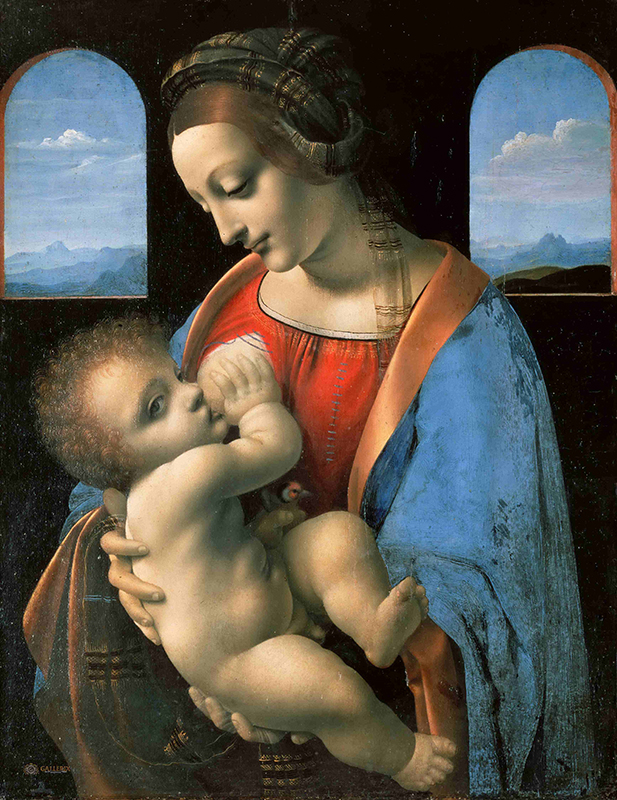

Mention should be made of Leonardo's enormously innovative and influential oil painting technique known as chiaroscuro. This method of using light and shadow mellows those precise outlines preferred by the more linear Florentine painters and enables intensity of coloring and depth, thereby creating the impression of natural three-dimensional figures in real space. We see this technique employed to great effect in Leonardo's Madonna and Child (the Litta Madonna) dated to the first half of the 1490s, for example in the lovely modeling of her tender face and in the way her fingers press against her child's skin. We also observe the two significant High Renaissance characteristics of harmony and balance in the perfectly simple, stable composition, with the tranquil figures arranged in a pyramid shape. As in the Benois Madonna, but here with more success, Leonardo uses windows to add a sense of light, depth, and endless space to what would otherwise be a somewhat claustrophobic composition.

And now it's on to Venetian Art (Rooms 217-222). Let's leave via the door opposite the Benois Madonna (and what an amazing door it is with its tortoise-shell veneer and gilded brass inlays) and then turn right, past Titian's distracting Danae (don't worry, we'll come back to her). We continue on through what were once small apartments intended for honored guests of the Imperial court but which now house treasures of Venetian art to Room 217. Here we move from madonnas to a murderess, albeit with a cause: Judith with the Head of Holofernes, an intriguing painting by the masterful, mysterious Giorgione (1477 – 1510) whose artistic brilliance was alas cut short by premature death, most likely due to plague. Together with his pupil, the slightly younger Titian, Giorgione was the founder of the distinctive Venetian school, which achieved much of its effect through color and mood and is traditionally contrasted with the linear disegno or draftmanship of Florentine painting such as we saw with Fra Angelico.

Only six paintings are currently attributed to Giorgione and we are now standing before the one that is considered the best work from the Hermitage's Venetian collection. Giorgione takes as his subject matter the biblical story of Judith, who in order to save her people from the Assyrian siege, dons her best finery, enters the enemy camp, charms and inebriates the Assyrian commander, and then lops off his head with his sword. In good Renaissance fashion, Giorgione depicts Judith in a state of serene tranquility despite the macabre beheading, and in good Venetian fashion, he uses light and color to create a rich, luminous effect. As is typical for this artist renowned for the elusive, poetic quality of his work, Giorgione refrains from standard iconographic elements that illustrate the story – we find no Assyrian camp, no table laden with empty wine bottles, and no encircled city. What we do find is a bare leg – a striking anomaly in the art of this time period. We really must admire how the slit in her rose garment is ornamented with golden embroidery, creating a delicate frame for that lovely leg. And only when we follow the leg down to the ground do we find the ghastly decapitated head, its dark curls entangled around her slender bare foot. What a painting!

Well, let's now return to that distracting Danae (Room 221), a masterwork by Giorgione's pupil and successor, the long-lived Titian (c.1490 – 1576). This unrivaled master of the Venetian school, known even in his lifetime as the Sun among Small Stars, has chosen for his subject matter a Greek myth, in which the King of Argos seeks to avoid an oracle foretelling his death at the hand of his daughter's son by locking away that as yet childless daughter, the hapless Danae, in a fortified tower. Yet fate is not so easily sidestepped, and Zeus appears to the imprisoned maiden in the form of a golden rain, impregnating her. Medieval images of Danae depict her fully clothed, catching the golden rain in her apron. And if we call to mind that iconic, although in comparison rather bloodless goddess from The Birth of Venus by the Florentine master Sandro Botticelli, we see how far our Venetian has moved things along in the area of the female nude. This was accomplished under the, shall we say, fig leaf of depicting an ancient Greek myth since such mythological nudity was sanctioned by classical precedent and thus deemed acceptable. In fact, the model for our Danae was most likely a courtesan. Well, before us we see the lovely, languid maiden lying on white bedding enveloped by a bower of luxurious crimson drapery, wearing only a ring and a bracelet, her face half in shadow, her body fully exposed. The unattractive crone of a maidservant, whose rough ugliness highlights Danae's luminescent beauty, holds out her apron to catch the gold coins raining down from thunderous clouds out of which Zeus' bearded head can be seen peering. But significantly, Danae does not notice the godly intruder as her gaze is transfixed by the raining gold. This brings us to the generally accepted meaning of the painting: the corrupting power of money. In the words of the Greek aphorism: "It was gold that bent the will of Danae. No need for a lover to pray to Aphrodite, if he brings money to offer."

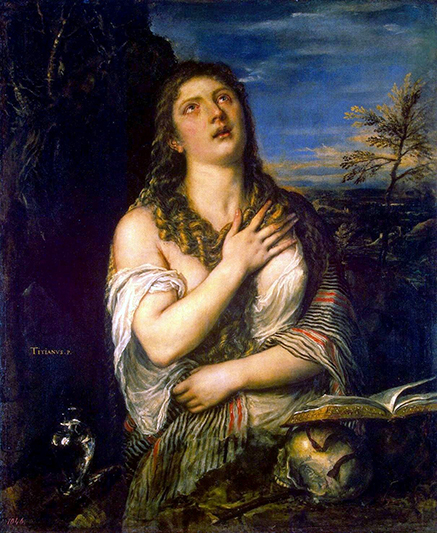

There are other magnificent Titians here including The Repentant Mary Magdalene and the quite late and expressive St. Sebastian, but let's move on through the next room past two of those Small Venetian Stars, Tintoretto with, among other works, his St. George on a majestic white horse slaying a bestial dragon and the great colorist Paolo Veronese's sparsely powerful Lamentation. We proceed through the following modest room containing glass objects and lace to thereafter turn right down the corridor, on our left the charming, pale blue, window-bedecked Arch over the Winter Canal, which connects the Old Hermitage with the Hermitage Theatre (only accessible during performances) and which offers superb views.

And thus we arrive at the Raphael Loggia (Room 227). Our collecting Empress, Catherine the Great, was highly impressed by color prints she had seen of frescoes created by Raphael (1483 – 1520) at the behest of Pope Leo X for a loggia in the Vatican Palace. Since the loggia itself could not be purchased, Catherine decided to have the entire space copied. Thus, the architect Giacomo Quarenghi was instructed to build this wing according to the required specifications while a group of artists made careful copies of the frescoes themselves. The result, which we see before us, is a splendid and almost exact replica of the original loggia. Looking up, we notice that the vaults are decorated with Biblical scenes, starting with images of creation – especially charming is the depiction of God standing among the animals – and continuing on through various patriarchs and kings (the first twelve vaults) to finally reach the New Testament (vault 13) with depictions of the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the Baptism of Christ and the Last Supper. When we get tired of craning our heads to look up at this lavish ceiling, known as Raphael's Bible, it's worth admiring the intricately decorated walls that feature a plethora of human and especially animal forms (mice, owls, birds, snakes, fish, squirrels, etc.) interwoven with myriad flowers and foliage. Raphael's work, which best captures the ideals of the High Renaissance, is praised for the clarity of its forms and the exquisite classical harmony of its compositions, all of which we see demonstrated so congenially in this magnificent loggia. Catherine herself so admired the Italian genius that she ordered a portrait of the 'divine Raphael' installed over the door at the end of the gallery.

Retracing our footsteps back to the middle of the Loggia, we turn left into Room 237 with its burgundy walls and lofty skylight and make an immediate right into Room 229 with its impressive coffered ceiling in order to admire two authentic Raphaels. The tiny, circular Madonna and Child (The Conestabile Madonna), in an elaborate gilded frame probably designed by Raphael himself, is an early painting by this great artist, completed circa 1504, before he was twenty. Yet even at this inexperienced age, those traits that characterize Raphael's mature work can be identified: the pyramidal composition, the serene landscape, the naturalness of the figures, the loveliness of the Madonna, the harmonious combination of colors, and the overall perfection of the image. We can detect these same features in the Hermitage's second work by Raphael, The Holy Family (1505-1507), painted during his stay in Florence. Iconographically interesting is the fact that Joseph, who regards the young child with an air of skepticism, is depicted without a beard – a great rarity.

We retrace our footsteps back to this room's four-columned alcove and make a quick detour to Room 230 where the Hermitage's only piece by Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) is displayed. This third member of the High Renaissance Triad (along with Leonardo and Raphael), was an exceptional painter, sculptor, architect, and poet who himself rated sculpture above all other forms of art. And here we have an example of his work in this medium in the form of The Crouching Boy (early 1530s), probably intended for the Medici Chapel in Florence. Although rough and unfinished – the master's chisel marks are still visible on the marble's white surface – and with his bowed face half-hidden, this figure of a young boy is nonetheless poignantly expressive. Look how the taut muscles strain with repressed energy and how the boy's constrained pose follows the original form of the marble block from which it was hewn, creating an impression of both tension and inner strength.

Now let's make our way back to the dramatic Lute Player (c. 1595), an early work by Caravaggio (c. 1571 – 1610) located in Room 237, the first of the three skylight rooms of Nicholas I's New Hermitage. These impressive rooms, with glass ceilings and expansive deep red wall surfaces, were intended to display the largest of the collection's paintings – which indeed they still do today. Our Caravaggio, however is actually quite modest in size, and with this small but priceless work, we say adieu to the serene, perfected Renaissance with its idealized classical beauty and enter the dramatic, emotionally charged world of the Baroque, a style that was greatly influenced and developed by Caravaggio. Interested in capturing the real and not always beautiful world around him, Caravaggio combined accurate, detailed observation with an innovative, dramatic use of light and darkness, to create powerful images, and even in this early work these distinguishing characteristics are apparent. Dressed in a glowing white blouse, the young musician is clearly delineated from the dark background, whereby the dramatic, intense lighting from an invisible source to the left and the resulting shadows lend volume and weight to both the boy and the objects that surround him. Although handsome, the boy does not have idealized, standardized features, but rather is recognizable as a unique individual. Upon closer observation, the props which make up the still life are also not perfect: the pear is bruised, the sheets of music are crumpled. The song, accurately transcribed onto those sheets, is the once popular melody "You Know that I Love You", but alas, it seems unlikely that our curly-haired lad will be successful in his conquest: the lute is cracked, which is a metaphor for love that fails.

We are going to have to use some extreme self-discipline here as we continue through the skylight rooms, bypassing scads of intriguing paintings by world-class artists – Canaletto! Tiepolo! Goya! Velasquez! – but after all, this IS the vast and unmanageable Hermitage, and if we don't move along, we'll never finish by the time the guards start shooing people out. So let's trek to the end of the gallery and then turn right to reach the outstanding Rembrandt collection in Room 254.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 – 1669) is considered one of Europe's greatest artists as well as the most significant painter in Dutch history, renowned for his expressive use of light and shadow, his restrained color palette, and his psychological and emotional perception. Let's head past his version of the recumbent Danae (1636) hanging across from a charming depiction of his wife as the goddess of spring in Flora (1634), to the far end of the room where we find the monumental, moving Return of the Prodigal Son (1669). Rembrandt painted this masterpiece towards the end of his career and it was still in his studio when he died. The subject matter comes from the Gospel according to Luke, in which Jesus relates the tale of a young man who demands his inheritance from his father and then absconds to a far county where he squanders the money on riotous living until, running out, he falls into the severest poverty. Desperate but repentant, he returns to his father, who rather amazingly, runs to greet him, welcoming him home with open arms, saying "We should be glad: for this son was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found." It is this moment of reunion that Rembrandt has chosen to depict: the son has fallen to his knees, reflecting his shame and degradation, yet also his repentance. His back is to us, but we can still observe his dreadful condition in the dirty foot, ragged shoes, tattered clothing, and shorn head that rests against the father's chest. The magnanimous father, emerging from the shadows, enfolds this beggarly prodigal in his warm red cloak, his hands placed comfortingly, lovingly on the boy's back. The old man appears nearly blind, but surely Rembrandt has succeeded here in creating one of the most astonishing countenances in all of art history, a face that radiates the forgiveness, mercy, and compassion of God.

Now it is on to that other northern Baroque Master and acknowledged head of the seventeenth century Flemish school, Peter Paul Rubens (1577 – 1640), whom we reach by retracing our steps back through the Rembrandt room and then continuing on until we dead-end into Room 248, turning left into Room 247. Known even in his lifetime as the Prince of Painters and the Painter of Princes, Rubens exemplifies the extravagant Baroque style that emphasized dynamic movement, intense colors, monumental forms, and luscious sensuality. Like Rembrandt, he was quite prolific and worked in almost every type of genre and subject, including portraits, landscapes, and history paintings with mythological, allegorical, and biblical themes, all of which can be admired in the Hermitage's collection. Let's take a look at the master's Descent from the Cross (c. 1618) immediately to the left of the doorway. Rubens, in typical Baroque style, has chosen to portray the most dramatic and dynamic movement of this tragic event, when Christ's pale, illuminated body is suspended between heaven and earth. Together with the white, blood-spattered shroud that swirls around him, he forms the visual and ideological center of the spiraling, diagonal composition, a focus that is intensified by the ring of five people who surround him, their hands outstretched, their eyes focused on his limp yet muscular body – most notably John the Evangelist in his deep red robe, Mary Magdalene with her cascading blonde hair and sumptuously worked deep-rose gown, and the solemn figure of the Virgin Mary, who lightly supports Christ's body with her refined hand. All scenery has been swallowed up in the darkness that surrounds the group, creating a dramatic, yet austere work, a painting that implies sorrow and emotional devastation. We could admire a number of other impressive paintings by Rubens, such as his jovial Bacchus or the rather romantic Perseus and Andromeda if only, if only there were world enough and time. As an aside, this Perseus was the son of our lovely Danae and her unannounced golden visitor, and as fate would have it, he did indeed end up killing his grandfather, although accidentally, when a discus he threw in a competition went off course and fatally struck the unfortunate king.

On that sad note, we head back from the Rubens Room, through Room 248, and then on via the southern wing of Catherine's original Hermitage. Outside we see the lovely hanging garden, inside some charming Dutch winter landscapes and two gilded clocks that remind of how time is flying by and how much there still is left to see. So let's make our way as rapidly as possible to the third floor by turning left in Room 272 and then proceeding on past French landscapes by Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain until we reach Room 280, where exiting to the right we come to the staircase that brings us up to our destination. The interior architecture here is much more mundane – this part of the palace was intended for courtiers, ladies-in-waiting and the like – but these modest walls house some of the most important and beloved pieces of the entire collection.

Cézanne's paintings beckon to us enticingly through the door beyond a large portrait of Napoleon's wife Josephine by Francois Gerard, but in order to view the collection chronologically, let's turn left and make our way to the far end of this wing, passing by a number of French academic works that with their formal painterly style and historic and biblical subject matter give us a chance to appreciate what the Impressionists, whom we reach in Room 320, were working against.

The Impressionist movement takes its name from a painting by Claude Monet entitled Impression, Sunrise (1872) and the moniker was originally intended as an insult. We are so accustomed to seeing Impressionist images splashed on everything from umbrellas to bath towels that it is difficult to conceive how radical and revolutionary their work originally was and how disdainfully both critics and the public at large reacted to paintings like the ones on the walls before us. Their concepts stood in complete contrast to the accepted style of the influential French Académie des Beaux-Arts that featured carefully staged scenes depicting mythological, historical, or religious subjects with crisp outlines, invisible brushwork, and minute attention to detail. The Impressionists, au contraire, with their fresh colors and exquisite rendering of atmosphere, drew from life, and their subject matter was transitory light and the fleeting moment.

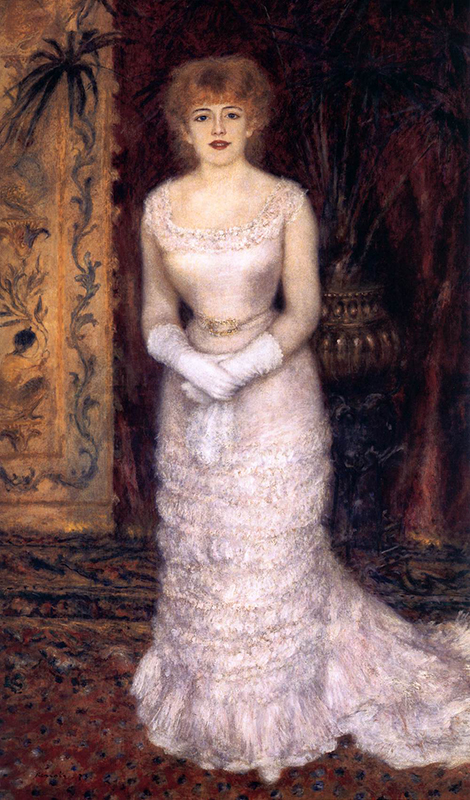

Before us in Room 320 we have the lightest of the Impressionists, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841 – 1919), known for his lovely depictions of women and girls – for example, Child with Whip, also in this room. This superb colorist once aptly remarked "Why shouldn't art be pretty? There are enough unpleasant things in the world," and we have a fine example of this pretty art in the Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary (1878). In good Impressionist fashion, Renoir has not tried to capture any deep psychological insights about the sitter, but rather spontaneous gestures, transient light, and delicate colors. He depicts the talented, strawberry-blonde actress from the Comédie-Française wearing an exquisite ruffled gown in shades of soft pink, with the hint of graceful movement and the shadow of a smile. After seeing this elegant portrait, Cézanne remarked that Renoir had "created the image of the Parisienne." As for Samary, whom Renoir painted numerous times and who sadly died of typhoid fever at the age of thirty-two, she said that "Renoir marries all the women he paints – but with his brush."

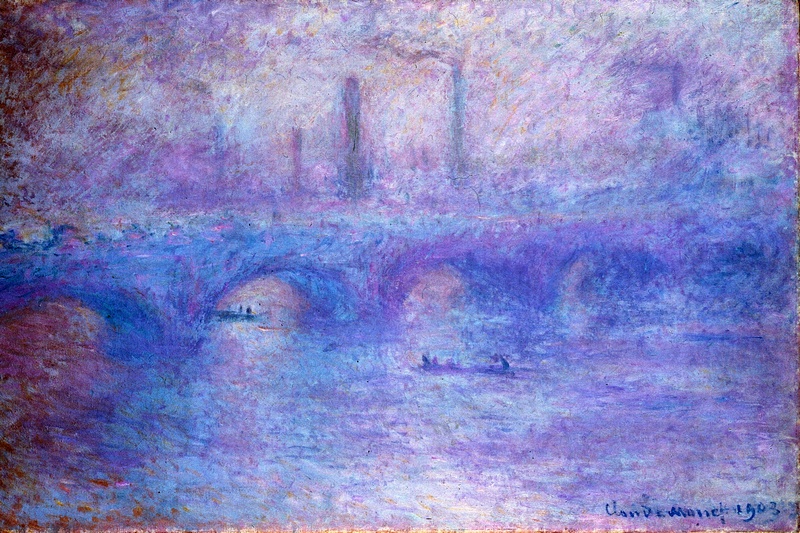

From here it is on to the king of Impressionists, Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) in Room 319. One of the artist's early works, Woman in the Garden (1867), with its fresh colors, feeling of spontaneity and absence of black, reflects first steps in this new manner of painting. Typical for the Impressionists, the subject matter is a charming scene en plein air – these artists preferred to work outdoors, capturing such carefree scenes as Parisian cafés, seaside holidays, boating parties, and bucolic landscapes, since here the fleeting effects of light could be more readily studied than in the artificial environment of the artist's studio. Along these lines, we can admire Monet's Pond at Montgeron (1876 – 1877) where, rejecting the rules of classical landscapes, our artist concentrates on capturing a momentary impression of transitory light, air, and water. But the truly grand work here is Waterloo Bridge, Effect of Fog (1903). In the first years of the twentieth century, Monet made several trips to London, and his room in the Savoy Hotel overlooked the Thames towards Waterloo Bridge. He painted this subject several times, studying the changes in perception caused by the fog. Indeed the central characters in this translucent work are not bridges and buildings but subtle light and luminescent lavender fog that shrouds and dissolves the surroundings in a ghostly mist. The two darker diagonal lines depicting small boats as well as several faintly discernible smokestacks are all that prevent the landscape from melting away into that superbly rendered mist.

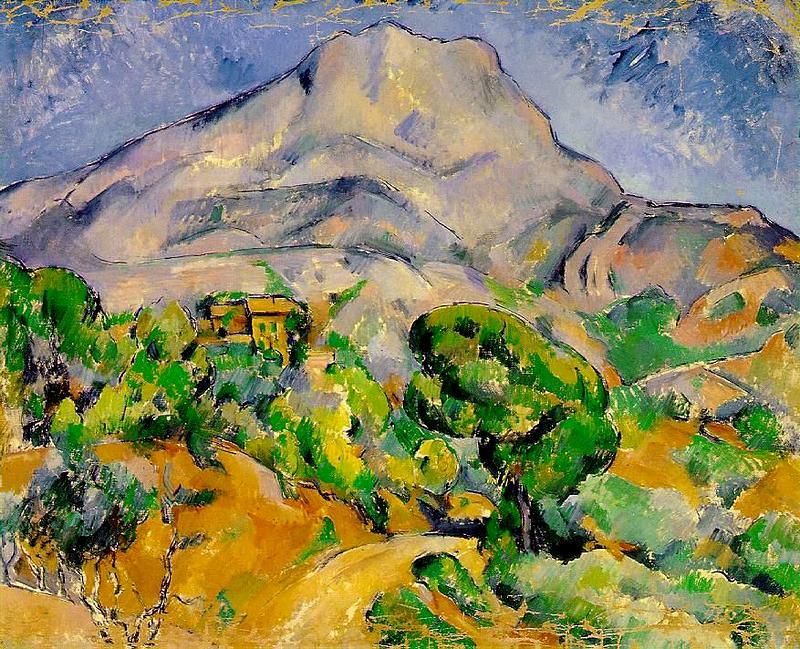

Let's now press on to Room 318 and the man known as the Father of Modern Art, the Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne (1839 – 1906). His work laid the foundation for the transition from heretofore essentially pictorial artistic endeavors to the new, radically different conceptual and abstract art of the twentieth century. After a stint in Paris, where he hobnobbed with the Impressionists, Cézanne returned to the city of his birth in the south of France, Aix-en-Provence. Here he restricted his contact with other artists in order to investigate structure, form, and color without outside influence in the attempt, as he said "to give the image of all we see, forgetting everything that has appeared before." One of his favorite subjects for this investigation was the massive Mount Sainte-Victoire, situated approximately eight miles to the east of Aix – he painted its broken silhouette over sixty times, from many different angles, between 1882 and the year of his death. Let's take a look at the Hermitage version, dating from 1896 –1898. Here we note Cézanne's interest in simplifying naturally occurring forms to their geometric essentials, structurally ordering what he observed into simple forms and color planes, moving further towards abstraction by using patches of color, almost like mosaic tile, to create form, weight and volume. His visible, short, diagonal brushstrokes are legendary. Cézanne applied them carefully, even tortuously, stroke by stroke, and they have been credited with changing the face of modern art in the way he used them to structure pictorial space.

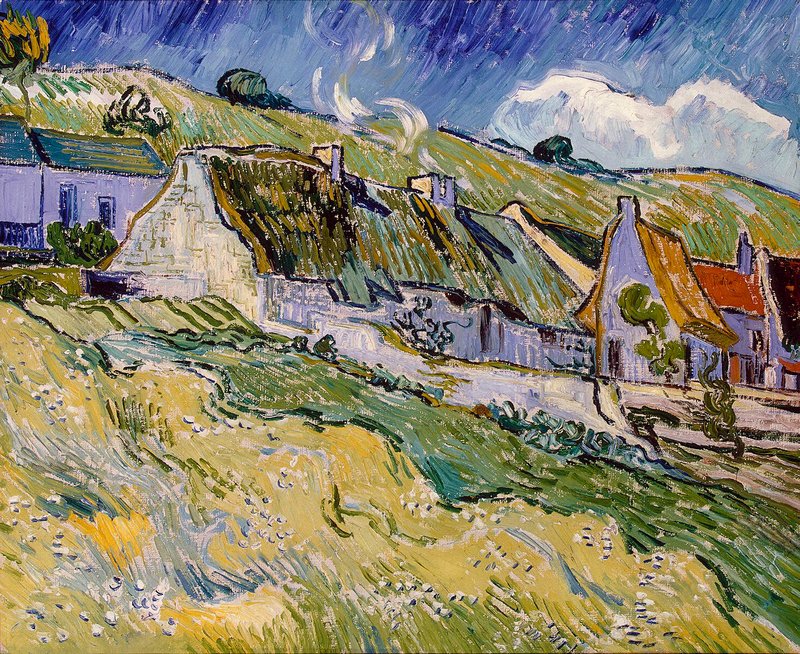

And now it is on to Room 317 and the unmistakable Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890), who during his exceptionally productive ten-year artistic career (1880-1890) created close to 900 paintings, of which only one sold during his lifetime. Let's take a look at his Cottages with Thatched Roofs, painted in the village of Auvers where Vincent moved in May 1890. He found the town to be "very pretty, there is countryside all around, typical and picturesque" and he immediately set out to paint the surrounding landscape with its homely peasant cottages, writing in one of his letters that "the most marvelous of all that I know in the sphere of architecture is huts with their roofs of moss-grown straw and a smoky hearth." In this painting we observe the humble dwellings clinging to the slope of the hill, their steep thatched roofs seem as much an organic part of nature as the hills and fields around them. There are no people in the scene yet the painting pulsates with a dramatic tension conveyed by the stark, dynamic brushstrokes, the vividness of the colors, the anxious rhythm of the composition, and the expressiveness of line. The intense blue sky, accentuated by the wisp of white smoke swirling from one of the chimneys, is not peaceful but charged with restless energy. Only two months after finishing this work, the great artist once again took his easel outside and after working all day on a painting of wheat fields, shot himself. Some of his last words were "the sadness will last forever."

Next we move on to Room 316 and van Gogh's one-time associate Paul Gauguin (1848 – 1903) – it was following a heated argument with Gauguin in 1888 that van Gogh famously cut off his left earlobe with a razor; after this incident, the two never saw each other again. Like van Gogh, who spent the first decade of his adult life plying a variety of trades such as an art dealer, teacher, and missionary, Gauguin came to his true profession relatively late in life. It was only in 1883 at the age of thirty-five that this successful Parisian businessman quit his job as stock broker to devote himself completely to what up until then had been a hobby – art. Eight years later, abandoning his wife and five children, Gauguin set sail for French Polynesia to escape what he saw as artificial, decadent European civilization in order to develop his own unique artistic style. We see the results in the fifteen paintings on the surrounding walls, in which Gauguin painted the enchanted Tahitian paradise that he had hoped to find rather than accurately capturing actual conditions on the island. Take, for example, Tahitian Pastorale (1892). The exotic landscape is depicted in bold, unrealistic colors – the sea is red, the sky is green – and flat simplified forms, creating a decorative rhythm accentuated by the unexpected tree branch that cuts across the girl's shoulders. Notably, Gauguin pays little attention to classical perspective and eliminates subtle gradations in color, thus rejecting two of the most cherished principles of art in vogue since the Renaissance.

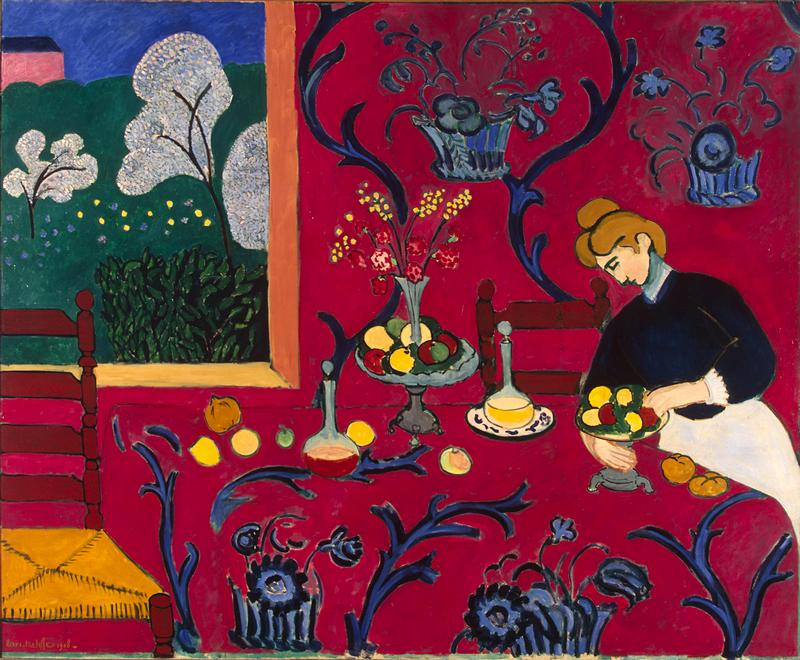

It would be heavenly to spend some time relaxing in Gauguin's tropical paradise, but Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954) awaits us in Rooms 343-345, straight ahead. The Hermitage has a magnificent collection of close to forty works by this seminal artist. Take for example the decorative, somewhat enigmatic The Red Room (1908) in which the dramatic, florid wallpaper spills over onto the table outfitted with typical Matissian props like fruit, vases, and candlesticks, or The Arab Coffee House (1913), the largest and most important work from his Morocco series, where with very flat space, a minimum of line and two goldfish, he has managed to capture the serene, somulent atmosphere of a lazy afternoon in an Arab cafe.

But let's now focus our attention on the iconic Dance (1910) where Matisse's unique and evocative use of color and form opened a new artistic language. This work, along with its counterpart Music on the opposite wall, was commissioned Sergei Shchukin, one of the most avid and forward-thinking Russian collectors of contemporary French art, to whom, thanks to the Russian Revolution's confiscation frenzy, the Hermitage owes much. Two years before starting on these works, Matisse wrote "What interests me most is neither still life or landscape, but the human figure. It is that which best permits me to express my so-to-speak religious awe towards life."We see this passion reflected in Dance, where five figures, dancing in a rhythmic circle and painted in an intense reddish-orange, are set against the flat, cool green of the earth and the intense blue of the sky, uniting Human, Heaven, and Earth. There is no superfluous line or emotion in this powerful, energy-packed work that is commonly considered a key point in both Matisse's career and in the development of modern art.

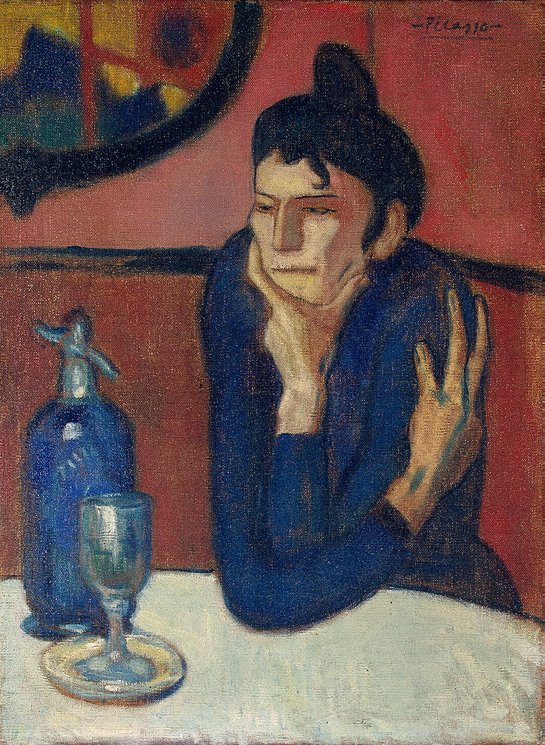

Finally, in Room 348, we reach the long-lived, prolific Spanish master, Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973), where we admire our last painting. Well, in a few short hours we have traveled from serene, harmonious gold-graced Madonnas and powder blue Renaissance skies to the modern world of loneliness, isolation, and emptiness encapsulated in Picasso's Absinthe Drinker. He painted this melancholy masterpiece during his second trip to Paris in 1901 when he was only nineteen. Picasso's artistic development was vitally affected by this Parisian voyage as it was here that he encountered and absorbed the techniques of Post-Impressionists such as Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin, artists whom he would never heard of had he remained in his native Spain. We see the results of these influences before us in the stark, flattened space, the strong flat colors, and the distinct black outlines, which combine to express discomfort, resignation, and loneliness. His solitary absinthe drinker sits alone at a table in a dingy cafe, her arms, with their exceptionally long hands, wrap around her angular body, expressing the isolation and introspection of the social outsider, cut off from the surrounding world.

But it seems we can almost read her thoughts. She appears to be musing "Mon dieu, this place is très immense, I've walked for miles, my feet are hurting, yet alas, I have viewed so few of the collection's three million pieces. What is there to do but drown my sorrow in absinthe, that green queen of poisons!" To which we can only reply, "oui, madame" and "salut!" as we follow the signs to the exit that lead us around the corner, down a functional staircase to the second floor and then through a hall hung with immense French and Flemish tapestries. But as we continue on to the exit, let us pause halfway through this hall before the painting of Catherine the Great who stands proud and assured in her regal glory. A curtsey and a tip of the hat are in order to this energetic, enlightened empress to whom we owe the magnificent Hermitage.