Dostoevsky's Petersburg: In the Footsteps of Raskolnikov

Time: approximately 3.5 hours

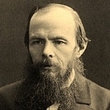

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) is one of Russia's most important writers and Crime and Punishment, in which a tormented young intellectual murders an elderly, loathesome pawnbroker, is one of his most riveting works. This book captures a distinctly Petersburgian atmosphere, but not one that features imperial palaces, classical architectural ensembles and promenades along aristocratic Nevsky Prospekt. Rather, Dostoevsky focused on Poor Folk and The Insulted and the Humiliated (as two of his earlier works were titled) and on the crowded streets, dirty alleys, cheap taverns and dilapidated rooms that these outcasts inhabited.

Who was Fyodor Dostoevsky?

One of the world's greatest authors, Dostoevsky is noted for his penetrating psychological insights, whereby he delved into such complex issues as poverty, exploitation, morality, suicide, free will, the essence of good and evil, and the existence of God. His works are marked by a great empathy for the poor and the downtrodden.

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky:

- was born on 11 November (old style 30 October) 1821 in Moscow where he spent the first sixteen years of his life.

- moved to St. Petersburg in 1837 at his father's insistence to attend the Military Engineering Institute in the Engineers' (Mikhailovsky) Castle, from which he graduated in 1843.

- left his stable position as a military engineer in 1844 to devote himself to writing and published his first novel, Poor Folk in 1846 to general critical acclaim.

- thought his life was over in 1849 when he was condemned to death by firing squad for his connections to a secret society of Utopian Socialists. He was carted from his cell in the Peter and Paul Fortress to be shot on Semyonovskaya (now Pionerskaya) Ploshchad, but as the Guards were raising their rifles, a messenger from the Tsar arrived commuting the sentence to four years hard labor in Siberia, which was followed by five years impressed service as a soldier in a Siberian garrison.

- was finally allowed to return to Petersburg in 1859, where he continued his literary career with The House of the Dead (1861), the first published novel to deal with Russian prisons.

- suffered from epileptic fits, which had a significant effect on his philosophy and conception of life. Characters with epilepsy appear in four of his novels.

- often fell into a perilous lack of funds and spent years in Europe hiding from creditors, where he indulged in his financially disastrous addiction to roulette – at one low point, he even pawned his patient wife's wedding ring.

- penned a number of classics of world literature, including Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov. His oeuvre includes fifteen novels and novellas, seventeen short stories, and numerous articles, and his works have been translated into over 170 languages.

- died on 9 February (28 January old style) 1881, just two months after completing his masterwork, The Brothers Karamazov. Tens of thousands of mourners attended his funeral procession.

We'll start our tour with a biographical focus, visiting the apartment museum where Dostoevsky spent the last years of his life. From there it's a quick metro ride to Sennaya Ploshchad ("Hay Market Square"), where both he and his anguished murderer roamed, brooding over philosophical questions raised by the dreadful poverty of the area. Then we'll trace the latter's footsteps as he sets off from his rented room towards the pawnbroker's flat with murder on his mind.

We start our tour at Vladimirskaya Metro Station, next to which we find a statue of our great writer, sunken in philosphical ponderings, with hands clasped and one knee crossed over the other. This imposing statue, erected in 1997, reminds us that the area around Vladmirskaya Square, although less readily associated with Dostoevsky than Sennaya Ploshchad, is where Dostoevsky spent the final years of his life and penned his last novel, The Brothers Karamazov.

Let's pay a visit to his last apartment now. Turning down Kuznechny Pereulok, which runs between the Metro station and the exuberant onion-domed Church of the Vladimir Icon, we walk by a row of Dostoevskian characters, most of whom are of grandmotherly age, purveying a motley assortment of mushrooms, cucumbers, berries and bouquets in order to enhance their meager pensions. Passing the Kuznechny Market on our right (it's worth taking a glance inside to catch a faint echo of the market atmosphere that pervades Crime and Punishment) we immediately reach the Dostoevsky Memorial Museum at 5/2 Kuznechny Pereulok.

Dostoevsky rented apartments in some twenty different buildings in Petersburg, never living in one place more than three years. Most of these apartments were in the inexpensive districts around the Church of the Vladimir Icon and Sennaya Ploshchad, and the reasons for these constant relocations were usually financial: our author experienced continual problems with money for the greater part of his adult life. Interestingly, one of his first apartments in St. Petersburg was in the very building we are regarding now, and he returned here some thirty years later, in October 1878, with his second wife, Anna Snitkina, and their two children. His flat, which is on the second floor, illustrates Dostoevsky's affinity for corner apartments, possessing a balcony and a view of a church.

Let's descend the few steps into the museum, buy our tickets and proceed up to the second floor. Here we find on the right two large rooms that feature exhibits dedicated to the writer's life and works, and on the left Dostoevsky's actual apartment, which has been restored to look as it did when the great author resided here. Let's take our time wandering through the rooms where we can admire his children's playthings, the small table on which the capable Anna handled business matters, and most impressively, Dostoevsky's study, the focal point of which is the large desk where he worked late into the night by candle glow, penning much of the magnificent The Brothers Karamazov. This is also the room in which he passed away and the grandfather clock is stopped at the hour of his death: 8:36 p.m. Especially touching are the words scrawled on a matchbox by his young daughter "Papa died today."

After absorbing all that the museum has to offer, let's retrace our steps back down Kuznechny Lane and take a quick peek in the Church of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God, where our deeply religious author was a parishioner. This yellow semi-baroque, semi-classical building was completed in 1769 and is famous for its elaborate iconostasis, which was designed by Bartomoleo Rastrelli, architect of the Winter Palace, and carved in the mid-eighteenth century.

Now let's retrace our steps back past Vladimirskaya Metro Station and across busy Vladimirsky Prospekt to the somewhat incongrous behemoth of a business center, completed in 2006, with the words Renaissance Hall emblazoned in Latin letters across its columned, glass façade. Tucked away beneath it, we find Dostoevskaya Metro Station, named in honor of our esteemed author. A relatively new station, opened during the last days of December 1991, we note that the architects attempted to capture a Dostoevskian atmosphere by employing old-fashioned lanterns and decorative wrought iron fencing reminiscent of the railings along St. Petersburg's canals. We'll hop on the metro for one station to Spasskaya, the last stop on the orange line, and follow the exit signs to the Sennaya Ploshchad, that is, to Hay Market Square. Thus, we emerge blinking into the central setting of Crime and Punishment.

Sennaya Ploshchad and its surroundings have changed much since Dostoevsky's time, so we will need to put our imagination in full throttle in order to envision the area that our author and his fictional characters once wandered about. Let's cross busy Ulitsa Sadovaya and take a seat on one of the recently installed benches, designed with tilting cart wheels at either end to evoke the square's market past, and make a few observations about Petersburg and Hay Market Square in the era of Dostoevsky.

Quotations

Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth.

I am convinced that not one of our writers, past or living, wrote under the conditions in which I constantly write.

When Dostoevsky was exiled in 1849, St. Petersburg still retained much of the aristocratic, orderly, imperial ambience of Pushkin's grand capital. By the time he returned one decade later, the city was enduring the initial upheavals of Russia's industrial revolution with all the related urban blight. The situation was compounded by the Emancipation Manifesto, signed by Alexander II in March 1861, which freed some twenty-three million privately held serfs across Russia. This long-overdue restructuring of Russian society nonetheless caused much turmoil and displacement. As thousands of newly freed serfs fled to Petersburg in search of work, the city's population burgeoned. Even in 1859, the year of Dostoevsky's return, Petersburg had a population of close to half a million and was the third largest capital in Europe after London and Paris. By 1869, the population had climbed over twenty-five percent to 667,000. Many of these new inhabitants crowded into the impoverished area around Sennaya Ploshchad.

This square, which was established in 1737 as a place where hay, oats, firewood and cattle were sold, quickly became known as the cheapest market in the city. By Dostoevsky's time, the resplendent baroque Church of the Assumption, erected on the square's edge between 1753 and 1765 (and unfortunately destroyed by the Soviets in 1961 to make way for the metro station), towered over a vast, crowded market. Morning to night, tradespeople loudly hawked all varieties of foods and products against a background of raucous sounds and rotten smells. The area teemed with farmers, peasants and merchants, with poor locals, petty thieves and prostitutes, with derelicts, drunks, and the destitute. Chaotic and crowded, dirty and discordant, Sennaya Ploshchad formed the antithesis to the imperial splendour of Palace Square a short distance away. And it was in this underbelly of the city that Dostoevsky set Crime and Punishment, originally published in twelve monthly installments in 1866. In the novel's first pages, he notes: "Close to the Hay Market, thick with houses of ill repute, the neighborhood swarmed with a population of tradesmen and jacks-of-all-trades who clustered in those central streets and lanes of Petersburg, creating such a panorama of motly characters that almost nothing or nobody could cause surprise."

Before starting on our quest to track the youthful murderer, let's take a look at the only building that has survived from the time when Dostoevsky frequented the area: The Guardhouse, a one-story yellow building fronted by a four-columned white portico located directly across Sadovaya Street from Sennaya Ploshchad Metro Station. This small but self-assured edifice was erected between 1818 and 1820 to maintain a police presence over the burgeoning market. Interestingly, this last vestige of the old Hay Market has a connection to our author. Arrested for violating censorship regulations he spent two days in detention here in 1874, which he passed reading Victor Hugo's Les Misérables.

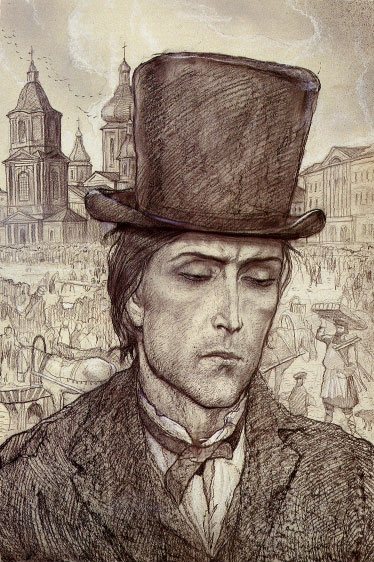

And now let's meet our protagonist, the twenty-three year old Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov. Our man – one can't really say "hero" - has a refined face and is remarkably handsome, above the average in height, slim, well-built, with beautiful dark eyes and deep chestnut-colored hair. Raskolnikov himself says that he is a poor student, sick and shattered by poverty. In fact, Dostoevsky notes that his clothes are in tatters, and that even a man accustomed to shabbiness would have been ashamed to be seen in the street in such rags. He has only one pair of socks.

Raskolnikov's adventure commences with a conversation overheard in one of the area's many dive bars, where a passionate student raises a utilitarian question regarding the life of a mean, merciless pawnbroker, the elderly Alyona Ivanovna:

"On one hand we have a stupid, senseless, worthless, spiteful, ailing old woman, of no use to anyone, on the contrary, harmful to all, having no idea herself what she is living for, and who will die in a day or two anyway... On the other hand, fresh young lives are being thrown away for want of help, by the thousands, and on every side! A hundred thousand good deeds and undertakings could be achieved on that old woman's money which she wants to leave to a monastery! Hundreds, thousands perhaps, of human beings might be set on the right path; dozens of families saved from destitution, from depravity, from destruction, from venereal hospitals - and all with her money. Kill her, take her money and with its help, devote oneself to the service of humanity and the good of all. What do you think, would not one tiny crime be blotted out by thousands of good deeds? For one life, thousands of lives saved from corruption and decay. One death, and a hundred lives in exchange - it's simple arithmetic! Besides, what value does the life of that sickly, stupid, malicious old woman have in the balance of existence! No more than the life of a louse, of a black beetle."

This is the philosophical premise that Crime and Punishment seeks to explore. Raskolnikov broods over the student's ethical proposal, which so closely echoes his own musings, and undertakes a trial run to the pawnbroker's apartment to lay the first steps for the woman's murder, but nonetheless doubts that he will actually find the strength to carry out the deed. "Good God!" he cries. "Can it be, can it be, that I will really take an axe, that I will hit her on the head, split her skull open... that I will tread in the sticky warm blood, break the lock, steal, and tremble, hide, covered in blood ... with the axe... Good God, can it be?"

Then after wandering about the oppressively hot city, as he is heading back towards his rented room, a chance event at a fateful corner of the Hay Market tips the scales. This corner is assumed to be at the entrance to Pereulok Grivtsova, which we reach by heading left from the Guard House past a lively variety of small shops selling mobile phones, cigarettes and schaverma to the next cross street. Here the weary Raskolnikov overhears the pawnbroker's naive, simple sister agreeing to meet a tradesman at that same spot on the following evening:

"All right, I'll come," said Lizaveta. Our protagonist's first amazement slowly turned to horror, like a shiver running down his spine. He had learned, he had suddenly and quite unexpectedly learned, that the next day at exactly seven o'clock in the evening, Lizaveta, the old woman's sister and only companion, would not be home and that therefore at exactly seven o'clock in the evening, the old woman would be home alone.

And with the feeling that he had no more freedom of thought, no will, and that everything had been suddenly and irrevocably decided, Raskolnikov stumbles back to his lodgings like a man condemned to death.

Let's follow him there. Heading down Pereulok Grivtsova, we soon reach the Griboedov Canal, nowadays a pleasant, winding, tree-lined waterway. Like the Hay Market, the canal presented a radically less sanitized view in Dostoevsky's day, and although its formal name then was Ekaterinsky, in honor of Catherine the Great, the locals nicknamed it the Drain as discharges from factories and courtyard cesspits poured into its murky waters, producing a revolting smell which hung over the area like a noxious cloud. The dreadful unsanitary conditions, combined with overcrowded housing, inadequate diet, damp climate, and general pollution turned Petersburg into the unhealthiest large city in Europe, with the highest death rate. Diseases such as cholera, diphtheria, smallpox, tuberculosis, typhus, and syphilis - not to mention chronic alcoholism - ran rampant and by the time of Crime and Punishment accounted for half of all deaths within the city boundaries.

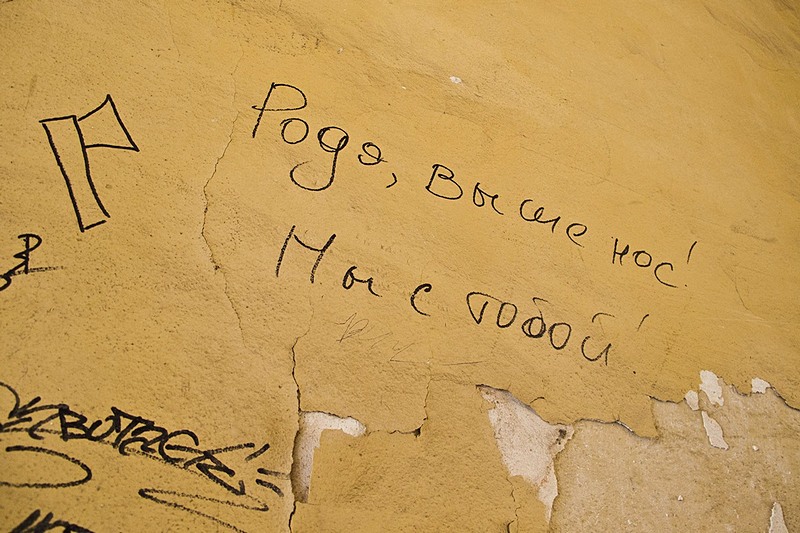

More on these dire living conditions later, but at the moment, we have no time to lose – our protaganist is slipping away from us, still consumed by the snippet of conversation he overheard in the Hay Market. So let's cross Demidov Bridge, make the first left thereafter into Grazhdanskaya Ulitsa and continue one long block until we reach Stolyarnaya Lane. There, on the corner across from us we see 5 Stolyarny Pereulok (also 19, Grazhdanskaya Ulitsa), towards which our protaganist wearily heads, and where we can admire a large, bronze relief of our author (installed in 1999), with furrowed forehead and clenched hands, under which a plaque reads

RASKOLNIKOV'S BUILDING

THE TRAGIC FATES OF THE PEOPLE

OF THIS PART OF PETERSBURG

SERVED

DOSTOEVSKY

AS THE BASIS FOR HIS PASSIONATE SERMONS

ON GOOD FOR ALL HUMANKIND

Raskolnikov has already disappeared into the building, and begun climbing the stairs to his humble abode under the eaves. Dostoevsky describes it thus:

His garret was under the roof of a tall, five-storied tenement building and was more like a cupboard than a room.... It was about six paces in length, and of a most miserable appearance, with dusty, yellowish wallpaper peeling off the walls, and so low-pitched that a man of more than average height felt uncomfortable in it as it seemed that at any moment he would hit his head against the ceiling. In fact, our protagonist's room was so small that he could undo the door latch without leaving his bed.

Unfortunately, access to the stairway leading to this garret has been barred by a metal door on Stolyarny Pereulok and a gate on Grazhdanskaya Ulitsa (if you are lucky enough to overcome these obstacles, the stairway is reached through the first door to the right of the Stolyarnaya entrance). We must therefore content ourselves with the general street view as we contemplate the living conditions during Raskolnikov's time, when there was an average of 247 people per building in the Hay Market area. Such astounding density was achieved by packing tenants into every possible space, including attics, closets, cellars, and under staircases. Enterprising landlords converted flats into flop houses that were crammed with rows of bunks. To achieve maximum utilization, these spaces were rented in shifts so that the same bunk might be occupied by two or three people over the course of twenty-four hours. As miserable as Raskolnikov was in his humble garret, it seems conditions could have been worse!

Well, not only was there a plethora of people in this working class district, there was also a plethora of dive bars and taverns, not surprising in a city where the per capita consumption of vodka was higher than anywhere else in Russia. In fact, a newspaper article from 1865 describes the street in which our protaganist lived as follows:

"There are sixteen houses in Stolyarny Pereulok. These sixteen houses lodge eighteen drinking establishments, so everyone who wants to take pleasure in the fiery and stimulating spirits has no need to look at the signs at all. Enter any house and you will find liquor everywhere."

And Raskolnikov at one time makes note of the unbearable stench from the taverns, especially numerous in that part of the city, and the drunks whom he constantly encountered whatever the hour.

This was the general atmosphere that our author viewed from the balcony of his second-floor apartment on 7 Kaznacheiskaya Ulitsa, a corner building one block to the left on Stolyarny Pereulok when facing Raskolnikov's building. Dostoevsky lived here from August 1864 to January 1867 (he also resided variously in flats at 1 and 9 Kaznacheiskaya Ulitsa, and his older brother Mikhail likewise lived for a time on this street), and it was here that he wrote the novel the action of which we are retracing. It was here too that he made one of the most important acquaintances of his life. Faced with an almost impossible deadline for his short novel The Gambler, he desperately searched for a stenographer to help him complete the gargantuan task, and thus, in October 1866, the efficient, capable, and patient Anna Grigorievna Snitkina, stenographic kit in hand, stepped into his life. With her expert help, the deadline was met, and less than six months later, she became his wife. Thanks to this remarkable woman, Dostoevsky's tenuous financial situation was eventually brought in order, and Anna was an incalcuable benefit to Dostoevsky in his work, aiding him in both the penning and publishing of his books. The world of literature owes her much.

And now let's return to our protaganist, who having spent the night in a heavy, laden sleep and the following day in a lethargic doze, suddenly realizes the late hour and falls into an extraordinary, feverish, distracted, haste. After all, he must manage to commit the ghastly deed before Lizaveta returns from the Hay Market. He dashes down the many stairs from his garret apartment to the courtyard below and pilfers an axe from the porter's dark, cramped room, which he hides under his wide, strong, summer overcoat. Let's follow him now as he continues down Stolyarnaya Lane, and share in his haste when he notices, glancing into a shop and seeing a clock on the wall, that the time is already ten past seven in the evening.

Hurrying along Stolyarnaya Lane, Raskolnikov crosses Kokushkin Bridge over the Griboedov Canal and continues straight for a short distance until he comes to Sadovaya Ulitsa. Here he turns right in the direction of tree-filled Yusupov Garden, one of the only green spots in the overcrowded Hay Market area. He notes that contrary to his expectations, he was not afraid at all. His mind was even occupied by irrelevant matters. And so having glanced at the mid-summer greenery, he becomes deeply absorbed with the thought of the construction of great fountains, and of their refreshing effect on the atmosphere in all the squares. Across from the Garden he turns right onto Prospekt Rimskogo-Korsakova, which he follows over two cross streets, and when reaching the third, Srednaya Podyacheskaya, stops: Here was the house, here was the gate...

Raskonikov has successfully arrived at his destination, 15 Srednaya Podyacheskaya (also 104 on the Griboedov Canal Embankment, gated entrances on both sides), described during his reconnaissance visit as a huge building which on one side looked on to the canal, and on the other into the street. This building consisted of cramped flats and was inhabited by all kinds of working folk - tailors, locksmiths, cooks, various Germans, girls making a living however they could, petty clerks, and so forth.

Once again, the tunnel-like arch leading to the atmospherically dilapidated courtyard is blocked by a metal gate, so we will have to wait outside as Raskolnikov slips into the door to the right of the gateway, ascends the dark, narrow staircase to the fourth floor and rings the bell to the pawnbroker's apartment. There is no answer. He rings again. Again no answer. Only on the third ring does the elderly woman unlatch the door and permit Raskolnikov into her small, spotlessly clean apartment.

A few minutes later, our protaganist pulled out the axe and:

Scarcely conscious of himself, swung it with both arms, almost effortlessly, almost mechanically, bringing the blunt side down on her head... Her thin, light, grey-streaked hair, as usual thickly smeared with grease, was plaited in a rat's tail and fastened by a broken horn comb which portruded from the nape of her neck. As she was so short, the blow fell on the very top of her skull. She cried out, but very faintly, and suddenly sank to the floor, although still managing to raise both hands to her head... Then, with all his strength he dealt her another blow and another, with the blunt side and on the same spot. The blood gushed as from an overturned glass, the body fell backwards. He stepped back, let it fall, and immediately bent over her face; she was dead.

Alas, due to Raskolnikov's late start, Lizaveta returns from her meeting at the Hay Market before he manages to quit the apartment and she too is slain by his bloody axe. Thus, not only the woman whose life was worth no more than that of a black beetle but also her naive, innocent sister are slaughtered, and the "simple arithmatic" of the student's tavern argument is thrown off kilter from the beginning.

Well, we've had a somewhat strenuous walk. I suggest we continue to the end of Srednyaya Podyacheskaya, where we once again meet the Griboedov Canal and, turning right, follow the canal for a calming stroll back to Sennaya Ploshchad, perhaps contemplating anew the proposition posed by the student in the tavern. By the way, we have progressed through only one-fifth of Crime and Punishment. Much of the rest of the novel reflects upon that very proposition, the validity of which Dostoevsky ultimately denies, and by the novel's end, Raskolnikov too returns along the canal to the Hay Market where he goes to the middle of the square, bows down and kisses the earth. Then he continues on to the police station, and with white lips and staring eyes, softly and brokenly, but distinctly says: "It was I... It was I who killed the old pawnbroker woman and her sister Lizaveta with an axe and robbed them."

A moment's pause seems appropriate....

Well, we don't want to leave our protagonist wallowing in the dreadful Petersburg slough where we have observed him for most of our walk, so let's finish with the thought that in the novel's epilogue, much like Dostoevsky some decades earlier, Raskolnikov is sentenced to years of hard labor in Siberia. In this distant location, which is depicted as natural, pure, and untouched by the crime and destitution flooding the Hay Market, our axe murderer is granted the hope of gradual renewal, gradual regeneration and of ultimate redemption through great striving, great suffering.

Addendum for die-hard Dostoevsky fans

Buy a rose from one of the kiosks on Sennaya Ploshchad and hop on the metro to Ploshchad Alexandra Nevskogo (again on the orange line, three stops east from Spasskaya). On exiting the metro, cross the square and enter Alexander Nevsky Monastery through the main gates. Turn into the Tikhvinskoe Cemetery (entrance fee) on your right. Here a number of illustrious personages are buried, including Tchaikovsky, Rubenstein, Mussgorsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Glinka. And here too you can lay your rose on Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky's tombstone, which is inscribed with a verse from the Gospel of John, in which Jesus says "Verily, verily, I say unto you, except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit."